Why Canadians don’t retire | Wealth Professional

“If we look at some of what registered psychologists have talked about, Canadians need to retire to something,” Staples says. “That’s particularly the case for men. As employees, we get a lot of our value, our self-worth, and our sense of how we contribute to the world from our jobs. Statistically, women are more likely to have a larger social network outside of the workplace. It’s often easier for women to transition into post work because they already have that network established whereas men will struggle more. So, we have to look at what their identity will be in retirement. I think that’s where financial advisors can really add value, by beginning that conversation around retirement identity.”

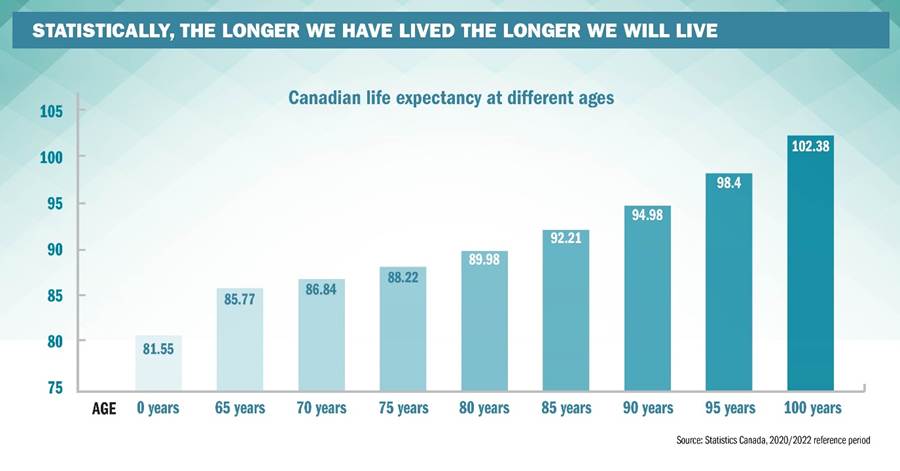

Of course, financial foundations are key to establishing that retirement identity. In that area, too, Staples notes the challenges that many Canadians face. She cites research conducted by G Schellenberg and Y Ostrovsky in the leadup to the GFC which noted the importance of access to a pension plan — ideally a defined benefit pension plan — in helping people feel secure enough to retire. Over the past three decades, Staples says, we have seen declining pension access in Canada. That lack of access, she says, is a key reason why fewer Canadians are retiring early. At the same time, Canadians are living longer, meaning they have to save and budget for a longer retirement, often without the support of an employer-sponsored pension plan.

Many Canadians are entering pre-retirement with considerable amounts of debt, too. Many are also aging with the expectation that their CPP and OAS benefits will function as their pension income — rather than just a backstop against dire poverty. Staples says that the income cohort between roughly the average industrial wage and around $120,000 is where financial advisors can make a significant impact. That cohort, she says, lacks meaningful retirement savings, while carrying the highest percentage of debt relative to income and assets. This leaves them vulnerable to experience retirement income insufficiency without an employer pension. They may not be aware of their situation, either, as some expect government pensions to provide them with enough. They very likely have some serious challenges to overcome before they can securely retire, and advisors can help them a great deal.

The trouble, for advisors and advisory firms, is that this income cohort is not exactly profitable. Commission-based advisory services are less incentivized to help with the financial plans these Canadians need. Fee based advisors, at the same time, are incentivized to chase larger account sizes. In seeking solutions Staples says she has encountered pro-bono programs offered in the United States. While Canada is behind our US counterparts somewhat, Staples notes a few efforts such as the push by FP Canada to increase access to financial planning. The Financial Planning Association of Canada (FPAC) also has a pro-bono committee where members regularly volunteer their time to help build plans for Canadians

link